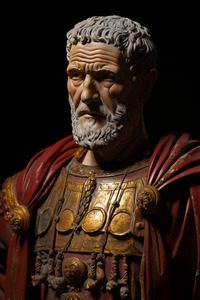

An Era Shrouded in Mysteries

The Middle Ages, also known as the Medieval period, spans over a thousand years of British history, commonly dated from the 5th to the late 15th century. This prolonged epoch is often referred to as the “Dark Ages” due to a scarcity of historical accounts compared to other eras. Yet the medieval and middle ages in Wales harbour intriguing tales of conquest and rebellion, the emergence of kingdoms, and the persistence of vibrant culture.

The Mysterious Early Middle Ages

As Roman forces withdrew from Welsh territory by 410 AD, a fog of uncertainty descended on the land. Historical details from the subsequent centuries are mired in legend and myth. What is known is that native Briton tribes filled the power vacuum, establishing small kingdoms and fighting relentlessly for supremacy. This marks the genesis of a turbulent yet definitive period in Wales’ national story.

The Mysterious Early Middle Ages

As Roman forces withdrew from Welsh territory by 410 AD, a fog of uncertainty descended on the land. Historical details from the subsequent centuries are mired in legend and myth. What is known is that native Briton tribes filled the power vacuum, establishing small kingdoms and fighting relentlessly for supremacy. This marks the genesis of a turbulent yet definitive period in Wales’ national story.

Native Welsh Kingdoms Emerge

Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed and Gwent rapidly emerged as the most dominant of the warring Welsh kingdoms. Chiefs and warrior kings such as Cadwallon ap Cadfan and Rhodri Mawr defeated neighboring rulers and assembled the foundations of the Wales known today. Yet stability remained beyond grasp, as ambitious royals continuously vied for greater wealth, territory and prestige.

The Welsh Church and Laws

As Christianity spread, it brought literacy and new administrative systems. The Church in Wales became the center of learning, producing influential works of poetry, astronomy, theology and philosophy. Distinct Welsh laws emerged too, codifying rules on women’s rights, property inheritance, livestock reparations and other components of day-to-day living.

The Age of Conquest and Resistance

As the 11th century dawned, the Welsh kingdoms found themselves facing a new threat – the intrusion of Norman forces, later backed by the ascending English crown. What ensued was an era defined by invasion, domination and the defiant struggle to maintain Wales’ distinct national identity.

The Norman Arrival

The Norman conquest of England in 1066 brought Welsh territories under the scrutiny of the ruthless Marcher Lords. Norman barons hungry for land eyed the fertile Welsh plains. When King Edward I ascended the English throne in 1272, Wales faced an existential threat.

Wales Under Siege

Edward I sought to conquer Wales entirely through brutal war, restrictive laws and the construction of mighty castles. Welsh rulers like Llywelyn the Last fought valiantly but fell victim to Edward’s campaigns. By 1283, Wales was under English rule, its people suppressed yet undaunted.

Glyndŵr’s Rebellion

In 1400, Wales found an new champion in the charismatic Owain Glyndŵr. He united Welsh nobles and farmers alike, winning several victories before his rebellion ultimately failed. Yet he remains an icon of Welsh defiance, his banner proudly flown to this day.

Wales in the Late Middle Ages

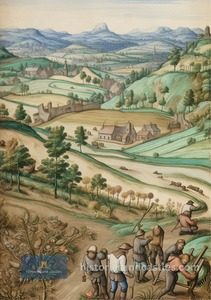

By the early 1400s, Wales was firmly under English dominion, its once mighty kingdoms reduced to scattered lands. King Henry IV consolidated his grip, incentivising English nobility to settle Welsh territories. Yet flames of Welsh identity and culture persisted in everyday rural life, song and faith.

Unrest and Integration

With independence lost for centuries to come, the late Middle Ages saw Wales progressively realigned with English structures of power. As locals bristled under the taxes and exploitation, sporadic rebellions continued to stir, often with bloody outcomes.

The Black Death Arrives

In 1349, the bubonic plague reached Wales, causing disproportionate chaos. Native customs like the tribal ‘ffestiniog’ ceremony became prohibited as English nobles and clerics stamped their authority. As the death toll mounted, many clung to superstitions, prayer and revolt to vent despair.

Cultural Life Endures

As castles multiplied and new market towns prospered, Welsh culture found expression in remote villages. Bards kept ancient legends alive by oral transmission. Plays, music and poetry praising Welsh heroes, satirising occupiers and romanticising past glories regaled locals across the country.

The Making of a Nation

For Wales, the Middle Ages represented an era of turmoil, resistance and the emergence of an enduring national identity. The centuries between the 5th and 15th centuries significantly shaped the Wales known today.

Conflict Forges Unity

As kingdoms rose and fell, and Norman conquerors imposed foreign rule, the Welsh were welded together in their stubborn fight for independence. Though Crushed militarily, concessions had to be made by rulers to local customs and languages.

Persistence of Culture

The medieval epoch endowed Wales with many of its national symbols and institutions. Be it the Welsh longbowmen, the bardic storytelling tradition or figures of resistance like Glyndŵr and Llywelyn, this was the crucible that forged the essence of Welsh nationhood.

A Defining Era

The turbulence that engulfed medieval Wales also delivered milestones in its economic development, civic structures, laws and church life. By the time Henry VIII dissolved Welsh dioceses in the 1500s, Wales stood proud as a distinct country with its own storied history and identity.

Related Articles

The Middle Ages: The Time Period Between Classical and Modern

The social structure and cultural norms in Europe during the Middle Ages played an integral role in shaping the everyday lives of those living in the era.

The Middle Ages in England

The Middle Ages in England span from around 500-1500 AD, covering over 1000 years of English history.