The Statute of Rhuddlan, implemented in 1284, was a pivotal development that paved the way for the legal assimilation of Wales into the Kingdom of England following King Edward I’s conquest. Whilst encompassing relatively technical administrative measures, the repercussions of this medieval statute proved far-reaching and enduring, positioning Rhuddlan as a cornerstone in the progress towards an incorporated Wales under English governance.

English unification and conquest: How the Statute of Rhuddlan shaped medieval Britain

Backdrop of conflict in Wales

In order to appreciate Rhuddlan’s significance, it is important to understand the backdrop of turbulent conflict between the rulers of Wales and England’s ambitious Plantagenet kings in the late 13th century. Rhuddlan was implemented shortly after Edward I‘s decisive conquest of the native Welsh princes, most notably the last sovereign ruler of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Edward’s victory built on over a century of intermittent warfare as English monarchs sought to force the submission of Welsh territories already notionally under their overlordship.

England’s might versus Wales’ autonomy

The asymmetric power balance saw the more unified and richer Kingdom of England attempt to dominate the smaller Welsh principalities from the time of the Norman Conquest onwards. Yet repeated Welsh uprisings under defiant princes underscored these rulers’ desire to retain autonomy over their ancient lands against encroaching English influence. The conquest and Statute decisively tilted this volatile rivalry in England’s favour.

Implementing English frameworks

At its core, Rhuddlan imposed English administrative models, legal jurisprudence and governance on Wales, abolishing prior Welsh laws. Wales was now partitioned into counties and placed under royal sheriffs and courts of the English style. Whilst seemingly bureaucratic measures on paper, they fostered far-reaching cultural change and set precedents for ruling Wales within English frameworks for centuries hence.

King Edward’s conquest of Wales

Earlier English advances

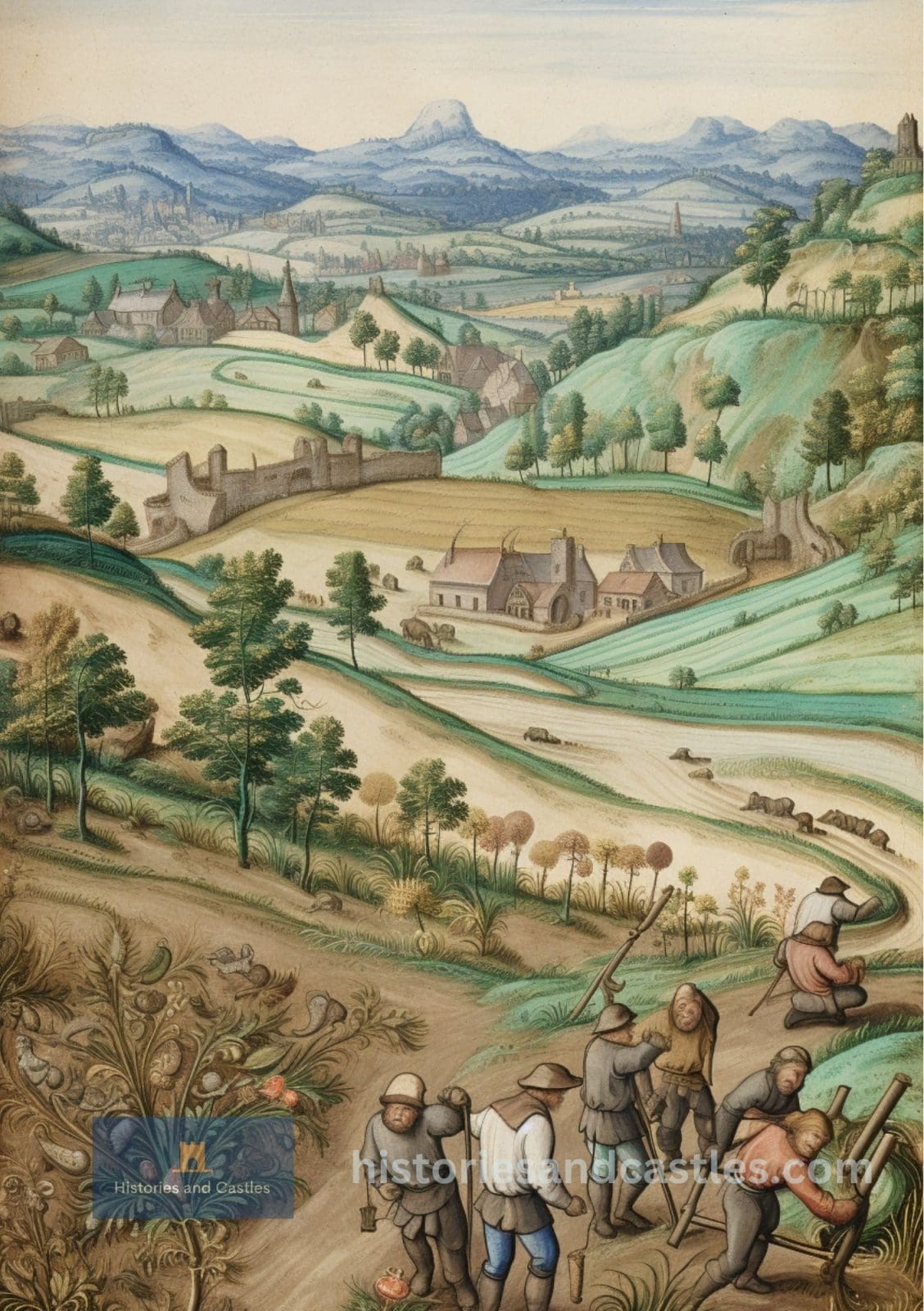

Prior to Edward I’s decisive 1277 and 1282 campaigns into North Wales, earlier English rulers had already made substantial advances in exerting control over Welsh territories. English nobles along the Welsh border had pushed outwards, often encroaching on pastoral and arable lands claimed by Welsh principalities. By the 1200s, most Welsh princes paid homage to the English crown, albeit often reluctantly.

Ascent of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

The mid-13th century saw renewed Welsh defiance under Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, who united most Welsh polities under his leadership and declared himself ‘Prince of Wales’. Llywelyn forged a virtual pan-Welsh alliance cemented by his marriage to Lady Eleanor de Montfort, daughter of the late English baron Simon de Montfort. This was an act of boldness verging on provocation towards King Henry III.

Edward’s campaigns to subdue Wales

When Edward acceded to the throne in 1272, one of his foremost aims was to elicit Llywelyn’s obedience. Edwards’ first Welsh campaign in 1277 resulted in Llywelyn agreeing to drastic terms curtailing his autonomy, albeit being allowed to retain the title of Prince of Wales. Continued Welsh defiance prompted Edward’s second, decisive invasion of 1282 which left Llywelyn slain in battle and Welsh military resistance shattered by 1283. The Statute of Rhuddlan was implemented the following year to consolidate Edward’s sovereignty over Wales.

Impact on Welsh autonomy and identity

Edward’s conquests enabled the English crown to drastically curtail symbols of Welsh princes’ autonomy, identity and cultural separateness from England. The deaths of both Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and his brother Dafydd in 1283 eliminated the last ruling figures who might have continued native Welsh dynastic resistance. Wales’ forcible reincorporation into Plantagenet royal administration could now proceed apace.

Terms of the Statute of Rhuddlan

Imposition of English common law

The single most crucial provision was the extension of English law and legal precedents into Welsh territories. Henceforth the populace dwelling in Wales would be adjudicated by English common law in royal courts, presided over by newly-appointed English sheriffs and bailiffs. This entailed abolishing Welsh customs based on native codes of law that had endured for centuries beforehand.

Administrative divisions on English model

The Statute carved up Welsh regions into new shires modelled on English counties, each under the jurisdiction of a sheriff, magistrates and courts mirroring those across the border. This facilitated standardised administration that integrated once-autonomous Welsh cantrefs into the Kingdom of England’s governmental structures. Through this measure, Wales was strategically divided into units easier for Plantagenet office-holders to monitor and control.

Restrictions on Welsh landowning rights

Special clauses stipulated that only English subjects had full rights to acquire land or leases in the new shires without Crown permission. This struck at the heart of Welsh nobles’ traditional prestige and autonomy as territorial magnates. Edward sought to entice his own followers to dominate landholding and minimise potential for future Welsh revolt. The measure would also encourage ongoing English settlement.

Cultural implications

Beyond the immediate administrative changes, the Statute set crucial precedents for ruling Wales within English legal frameworks for centuries thereafter, accelerating a process of cultural assimilation. As resisting the Statute’s measures carried the threat of treason against the Crown, many Welsh gentry eventually acquiesced to adopting English administrative and cultural norms to preserve their status.

Effects of the Statute

Consolidating English rule

The Statute enabled King Edward I to consolidate his hard-won sovereignty over Wales. By dismantling prior Welsh administration and rulership structures, Edward could install his own loyal vassals and extend bureaucratic oversight. This facilitated managing Wales as annexed territories of the Crown rather than through appeasing semi-independent Welsh princes as in the past.

Facilitating cultural assimilation

With Welsh nativist law codes abolished and English common law now the sole legal system, Wales was put on a gradual path towards cultural assimilation after 1284. Over the ensuing decades and centuries, use of the English language spread while adoption of English agricultural practices, architectural styles and civic governance models also accelerated.

Enabling English settlement

By restrictively restructuring Welsh land ownership and tenancy rights, Edward’s Statute encouraged a steady influx of English settlers, clerics, lawyers and royal officials into newly “pacified” Welsh shires. This settlement activity gradually transformed Wales’ demographic make-up and consolidated the English Crown’s control.

Reactions: from stoic acquiescence to intermittent rebellion

Many descendants of native Welsh royalty who wished to preserve estates and status had little choice but acquiescence with the Statute’s conditions, however resentfully. But the harshness of English rule also fed periodic armed rebellions aiming to destabilise English hegemony, such as Owain Glynd?r’s fiery uprising around 1400, although ultimately unsuccessful.

Long shadow over governance of Wales

The administrative template forged by Rhuddlan remained highly influential as the basis for structuring royal governance of Wales across subsequent medieval centuries. Even after England’s break from Rome under Henry VIII, Wales’s status as annexed territory subject to English law and oversight continued largely unaltered until the 20th century.

Long-term Significance

Setting influential precedents

The administrative model imposed on Wales by Rhuddlan remained a template for English governance of the territory across subsequent centuries. Wales was clearly cemented as an annexed domain to be ruled through the Crown’s representative bodies along English lines, rather than as a semi-independent ally or client state.

Building an enduring legal union

By formally extending English law and courts to Wales from 1284 onwards, Rhuddlan built firm foundations for an incorporated Wales bound to England by common legal jurisdiction. Though the intensity of assimilation ebbed and flowed, Wales remained under the umbrella of English law for over 700 years thereafter.

Encouraging ongoing cultural integration

The combined effect of legal, tenurial and administrative measures was the steady diffusion of English cultural mores into Welsh life across decades and centuries after Rhuddlan, most notably the English language. Yet a resilient sense of Welsh identity also endured, whilst simmering anti-English resentment sporadically sparked revolt.

Complex constitutional status

Despite Wales becoming de facto England’s first colony, its exact constitutional position long remained opaque and complex. Unlike Ireland or Scotland, annexed Wales was not a separate kingdom but also lacked home rule. Ambivalence towards according Wales greater autonomy persisted into the democratic era.

Eventual administrative devolution

Only in the late 20th century did Wales finally gain some self-governance in the form of its own legislature and executive. Yet the complex legacy bequeathed by centuries of English legal jurisdiction and cultural intertwining sparked ongoing disputes on the appropriate balance between Welsh devolved autonomy and sovereignty retained at Westminster.

A pivotal development

The Statute of Rhuddlan marked a pivotal moment in the history of both Wales and medieval England more broadly. Edward I’s conquests may have broken the military strength of princely resistance, but it was the Statute which paved the way for lasting English administrative hegemony and seeded gradual cultural assimilation.

Laying foundations for incorporation into England

By constructing an English-style governmental framework and imposing law codes familiar across the border, Rhuddlan laid solid foundations for Wales’ eventual incorporation into the Kingdom of England as a territorial dominion. The conquest provided the opportunity, but it was Rhuddlan which put in place the legal levers which, over time, embedded English influence into Wales’ fabric.

Gradually eroding symbols of Welsh autonomy

The Statute led to steady erosion of touchstones of Welsh autonomy: native leadership, law, language, land rights and more. Generations of Welsh nobles and commoners faced little choice but to operate within English structures, adopting English customs and phrases as pragmatic means of advancement. A creeping but inexorable process of cultural absorption was set in motion from the 1280s.

Modern legacy

The ripples of Rhuddlan as a formative development for Anglo-Welsh relations are still evident today in disputes over Welsh devolution and governance. Whilst an incorporated Wales was perhaps inevitable given asymmetric power relations, Rhuddlan enshrined particular pathways to assimilation which continue to shape debates centuries later. The complex constitutional status of Wales owes much to the towering legacy of this medieval statute imposed by a conquering English king.

Read more about Statute of Rhuddlan

Discover more from Histories and Castles

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.