Fear Beneath the Surface

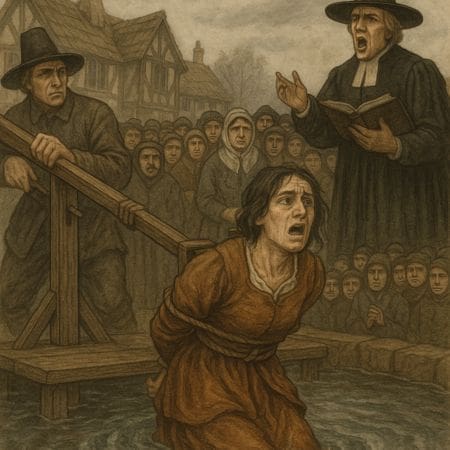

Picture an English village pond in the dawn light. Mist curls over the still water. Birds stir in the hedgerows, and the villagers gather, breath visible in the chill air. But today, they are not here to fish or fetch water. They’ve come to watch a woman tied and thrown into the pond. If she floats, she’s a witch. If she sinks and drowns… she’s innocent.

So ran the logic behind one of history’s most chilling practices: trial by water. Known variously as “witch ducking” or the “swimming test,” it was just one of several brutal ordeals devised to extract a confession — or simply confirm a suspect’s supposed guilt.

The medieval and early modern periods in Britain were times of deep superstition and fear. Between the late 1400s and the early 1700s, waves of witch hunts swept through the country. Communities terrified of famine, plague, or misfortune desperately sought scapegoats. And time and again, these scapegoats were women — often poor, elderly, or outspoken.

Let’s dive beneath the surface of this grim chapter of British history, explore the mechanics of water ordeals, and hear some true, haunting tales of those who faced the ducking stool or the pond.

The Origins of Trial by Water

The notion of water as a “truth-teller” stretches back centuries. In medieval England, the concept of the ordeal was rooted in the belief that God would not allow an innocent person to suffer unjustly. If a suspect endured pain without injury — or survived an impossible feat — it proved divine intervention on their behalf.

Water, as a symbol of purity, was believed to “reject” evil. Hence the twisted logic:

- If a person sank, it meant the water had accepted them, proving innocence.

- If they floated, it signified rejection by the pure element, proving guilt.

It sounds absurd to modern ears. Yet this idea thrived across Europe, surviving through medieval law and seeping into Tudor and Stuart England’s witch trials.

While trial by water was used for various crimes, from theft to heresy, it gained particular infamy in connection with witchcraft. By the 17th century, the swimming test had become an iconic feature of witch-hunting fervour.

How Witch Ducking Worked

Despite popular images of elaborate ducking stools, the swimming test was often quite rudimentary. Here’s how it generally worked:

- Binding: The accused’s hands were tied to her feet, or crossed in front of the chest. Some accounts mention rope tied around the waist.

- Blessing the Water: Priests sometimes blessed the pond or river, further underscoring the ritualistic nature of the act.

- Immersion: The suspect was thrown in.

- Observation: If she sank immediately, she was deemed innocent. If she floated or struggled at the surface, she was presumed guilty.

In practice, sinking often meant drowning — or near-drowning. Floating was, ironically, quite likely, given the air trapped in clothing or the suspect’s natural buoyancy, especially if wearing petticoats.

Important distinction: The ducking stool — often confused with the swimming test — was a different punishment. The stool involved repeatedly dunking a convict into water, used to punish scolds, gossips, or suspected witches after a verdict rather than to determine guilt.

Chilling Tales from British History

The Case of Grace Sherwood — A Tide-Turned Trial

Though Grace Sherwood’s ordeal happened in colonial Virginia, it’s worth mentioning because it perfectly illustrates how English practices crossed the Atlantic. In 1706, accused of bewitching livestock and crops, Grace was ordered to be “ducked.” Tied and tossed into a river, she floated, thus “proving” her guilt. She spent years in prison. Eventually released, she lived to old age — but never entirely escaped suspicion.

British settlers carried these customs overseas, ensuring the dark shadow of the swimming test stretched far beyond English soil.

You might like these

-

Advanced Potion Making Book – Magical Replica

£18.93 -

Norse Runes Viking Pendant Amulet

Price range: £9.99 through £12.99 -

Viking Rune Crow Pendant Chain Necklace

£13.71 -

Dragon Obsidian Pendant | Silver-Plated Dragon Necklace

£18.99

The Bideford Witches — Devon’s Grim End

Closer to home, we find the Bideford witches: Temperance Lloyd, Susannah Edwards, and Mary Trembles. In 1682, these three women from Bideford, Devon, were accused of witchcraft. Their confessions, extracted under pressure, included tales of imps, familiars, and diabolical pacts.

Though records don’t explicitly mention the swimming test in their case, Devon was no stranger to water ordeals. Local magistrates frequently ordered such tests to confirm suspicions. The Bideford witches were ultimately hanged, among the last in England to be executed for witchcraft.

Northamptonshire’s Ducking Stool — A Tool of Terror

Records from Northamptonshire reveal ducking stools used well into the 18th century. Public duckings took place on market days, turning punishment into entertainment. One account describes a woman ducked repeatedly until she lost consciousness — not necessarily because she was a witch, but because she was a “scold.”

Though ostensibly separate from witch trials, the punishment often overlapped, as suspicion of witchcraft and social transgressions blurred together.

The Witches of Manningtree — Matthew Hopkins and the “Witchfinder General”

No exploration of British witchcraft would be complete without Matthew Hopkins, self-styled Witchfinder General. During the English Civil War, Hopkins terrorised East Anglia, accusing dozens of witchcraft. He employed numerous “tests,” including pricking the skin for “witch marks,” forced confessions, and, on occasion, swimming trials.

Hopkins’s reign of terror ended only after the government began to question his methods. Nonetheless, the damage was done. An estimated 100 to 300 people died during his campaigns between 1644 and 1647.

Why Floating Wasn’t Always “Magical”

Today, floating seems innocuous enough — after all, it’s basic physics. But to early modern minds, the sight of a woman refusing to sink was proof of supernatural forces. Yet several natural factors played into the ordeal’s tragic outcomes:

- Clothing: Heavy gowns sometimes trapped air, creating buoyancy.

- Nervous Struggle: A panicking person might thrash or instinctively hold their breath, making floating more likely.

- Cold Water Shock: Cold water stiffened limbs, hindering sinking.

- Blessed Water: Some communities believed consecrated water would repel witches, adding divine significance to the test.

Ironically, even if a woman survived ducking, the ordeal itself could leave permanent injury or trauma. Broken ribs, dislocated limbs, and pneumonia were common consequences.

The Legal Decline of Water Ordeals

The tide finally turned in the early 18th century. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 effectively ended prosecutions for witchcraft in Britain by reclassifying witchcraft not as a supernatural crime, but as fraud. Those claiming magical powers faced fines or imprisonment rather than execution.

Gradually, the swimming test fell out of use. Yet remnants of the practice lingered in folk memory for decades. As late as the 19th century, mobs occasionally tried to “swim” suspected witches unofficially.

One historian records a near-ducking in Leicestershire in 1863, when a woman was accused of bewitching cattle. Only police intervention prevented her from being thrown into the village pond.

Witchcraft in Modern Britain: A Changed Legacy

Today, we look back at witch ducking with a mixture of horror and disbelief. How could communities inflict such cruelty on neighbours — often elderly women who’d done nothing more than quarrel, live alone, or tend herbs?

Yet echoes of those centuries linger. In modern Britain, paganism and Wicca are legally protected faiths, with thousands identifying as witches or magical practitioners. Far from hiding in fear, many celebrate their beliefs openly.

Nonetheless, witchcraft remains a potent symbol — in literature, film, and culture. Stories of ducking stools and swimming tests fuel countless novels and documentaries, feeding both fascination and cautionary tales.

These historic witch trials remind us how fear can twist reason and how communities can turn on individuals in search of someone to blame. Though Britain no longer dunks people in ponds to “prove” guilt, witch hunts, in metaphorical form, still happen — in tabloids, online mobs, or social media scandals. The machinery of suspicion and scapegoating is alarmingly easy to revive.

Beneath the Calm Waters

If you stand beside a serene village pond today, the ripples might look harmless. But beneath those waters lie centuries of fear, superstition, and injustice. The floating woman became a symbol — not of witchcraft — but of how fragile human mercy can be when panic takes hold.

The legacy of witch ducking, the swimming test, and other ordeals calls us to remember a time when purity was measured by drowning and when the very element that gives life became a tool of persecution.

May we keep learning from those dark waters — so that justice never again demands such a cruel test.

Medieval Magic

From enchanted pendants to legendary relics, this collection channels the magic, myth, and symbolism of the Middle Ages.

Whether you seek protection, wisdom, or just a touch of otherworldly style — you’ll find your talisman here.

Discover more from Histories and Castles

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.